Architecture

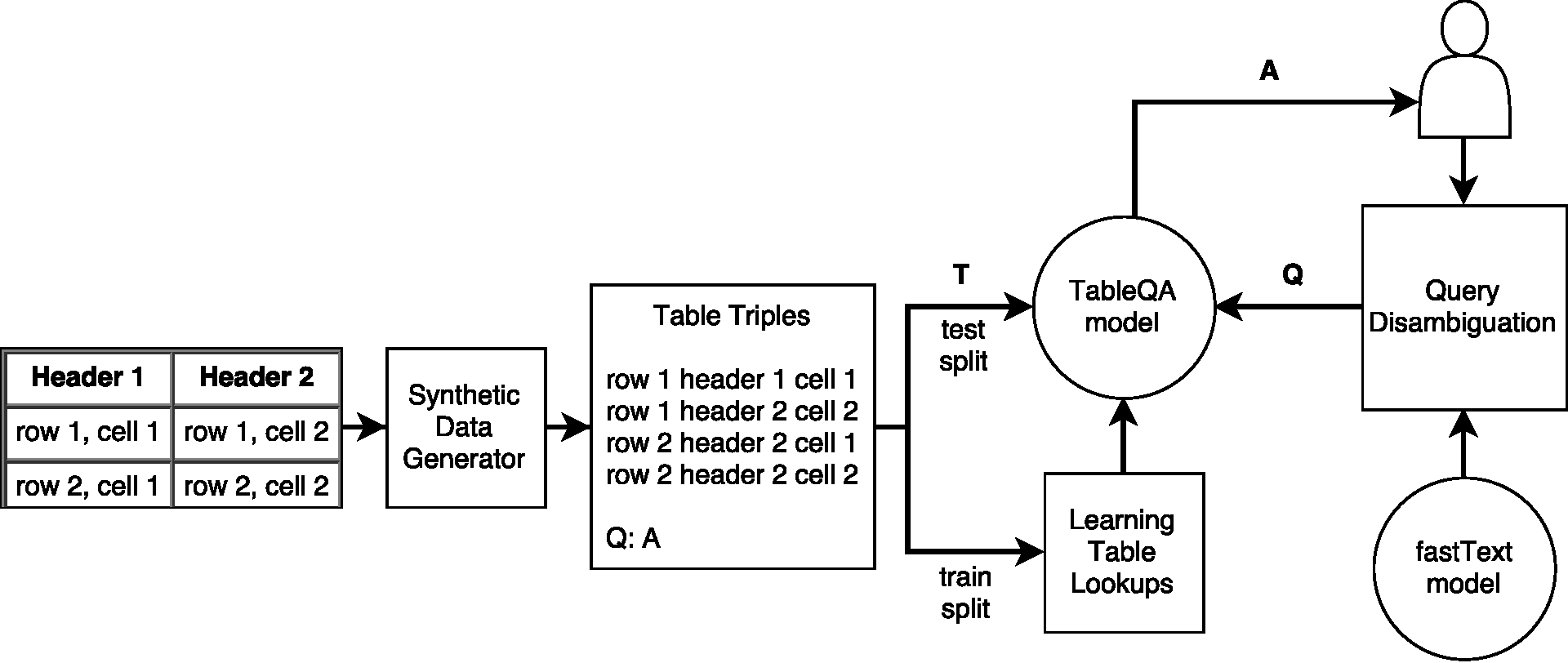

The architecture of our system for table-based question answering is summarized in Figure Figure 1 . Each of the individual components is described in further details below.

Table Representation

Training examples consist of the input table decomposed into row-column-value triples and a question/answer pair, for instance:|

Row1 |

City |

Klagenfurt |

|

Row1 |

Immigration |

110 |

|

Row1 |

Emigration |

140 |

|

Row2 |

City |

Salzburg |

|

Row2 |

Immigration |

170 |

|

Row2 |

Emigration |

100 |

Question : What is the immigration in Salzburg?

Answer : 170

Learning Table Lookups

Our method for question answering from tables is based on the End-To-End Memory Network architecture [4] , which we employ to transform the natural-language questions into the table lookups. Memory Network is a recurrent neural network (RNN) trained to predict the correct answer by combining continuous representations of an input table and a question. It consists of a sequence of memory layers (3 layers in our experiments) that allow to go over the content of the input table several times and perform reasoning in multiple steps.

The data samples for training and testing are fed in batches (batch size is 32 in our experiments). Each of the data samples consists of the input table, a question and the correct answer that corresponds to one of the cells in the input table.

The input tables, questions and answers are embedded into a vector space using a bag-of-words models, which neglects the ordering of words. We found this approach efficient to work on our training data, since the vocabulary for column headers and cell values are disjoint. In the future work we consider also evaluating the added value of switching to the positional encoding on the real world data as reported in [4] . The output layer generates the predicted answer to the input question and is implemented as a softmax function in the size of the vocabulary, i.e. it outputs the probability distribution over all possible answers, which could be any of the table cells.

The network is trained using stochastic gradient descent with linear start to avoid the local minima as in [4] . The objective function is to minimize the cross-entropy loss between the predicted answer and the true answer from the training set.

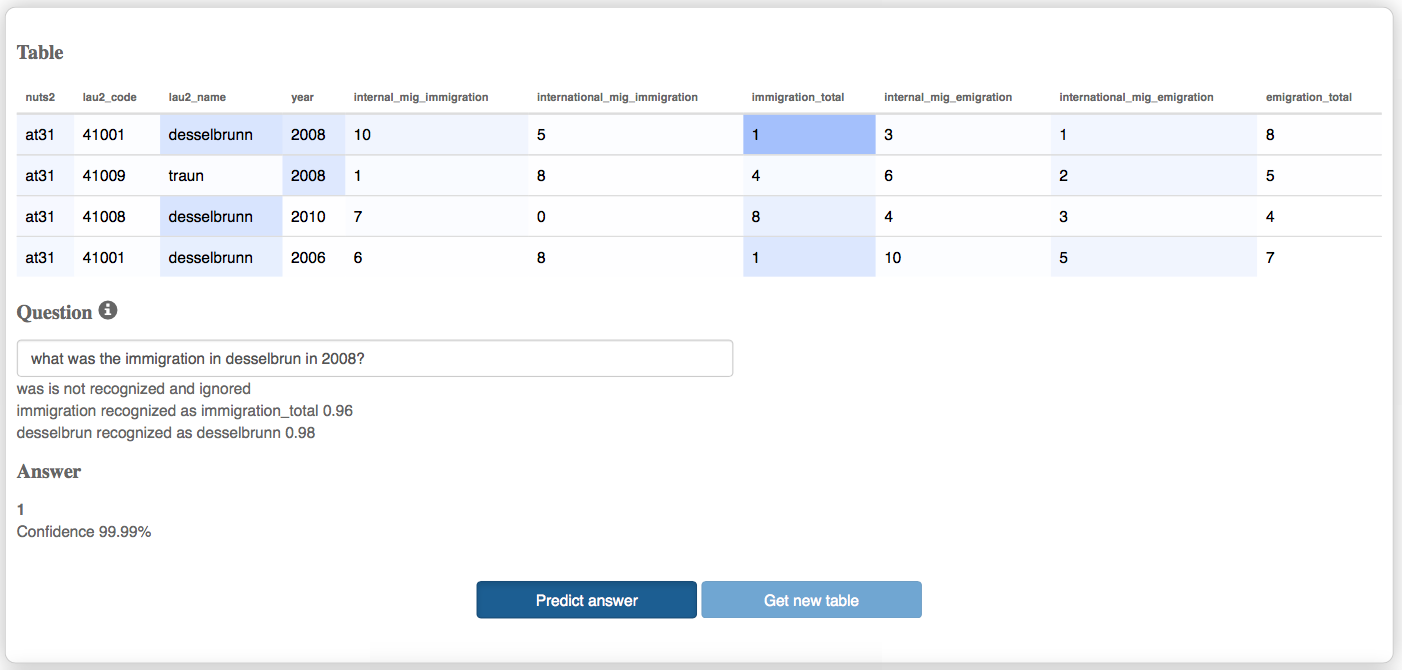

Query Disambiguation

Since users may refer to the columns with words that differ from the labels used in the table headings, we employ a fastText model [1] pretrained on Wikipedia to compute similarity between the out-of-vocabulary (OOV) words from the user query and the words in our vocabulary, i.e. to align or ground the query in the local representation. The similarity is computed as a cosine-similarity between the word vectors embedded using the pretrained fastText model.

fastText provides continuous word representation, which reflects semantic similarity using both the word co-occurrence statistics and the sub-word-based similarity via the character n-grams. For each of the OOV words the query disambiguation module picks the most similar word from the vocabulary at query time and uses its embedding instead.

In our scenario this approach is particularly useful to match the paraphrases of the column headings, e.g., the word emigration is matched to the emigration_total label. We empirically learned the similarity threshold of 0.8 that provides optimal precision/recall trade-off on our data.