Circular Economy Conceptual Model

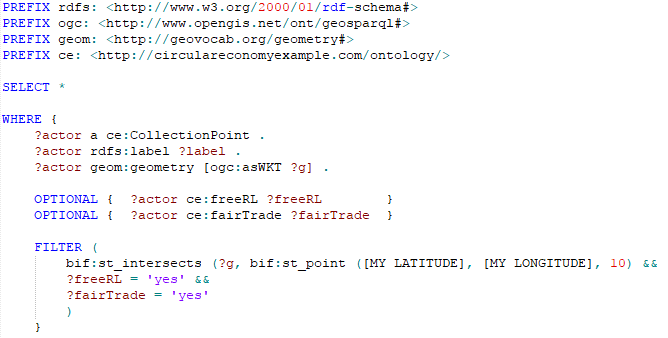

Taxonomy

A high-level taxonomy is constructed as a basis for understanding what processes, elements and activities are happening within the CE framework, see Figure 1 (adapted from [8] , [3] ).

Resources and actors are key elements for the circular economy (grey). Actors are the different companies or individuals. Resources are divided into two main CE categories: bio-based and technological . Resources are further broken down into a hierarchy of parts, starting with the whole part ( product ) ending with the smaller part ( chemicals, out of research scope). Even though products may consist of components, sometimes components can be considered as products elsewhere in the supply chain. When resources finish their use cycles, they must undergo different post-use activities (yellow); there are some restrictions for the post-use activities’ input materials i.e. only bio-based materials can be composted. Further, each product is tracked through a product biography using RFID or IoT technologies (cyan). Finally, ‘collaboration’ is a process occurring between companies and individuals (pink).

Ontologies

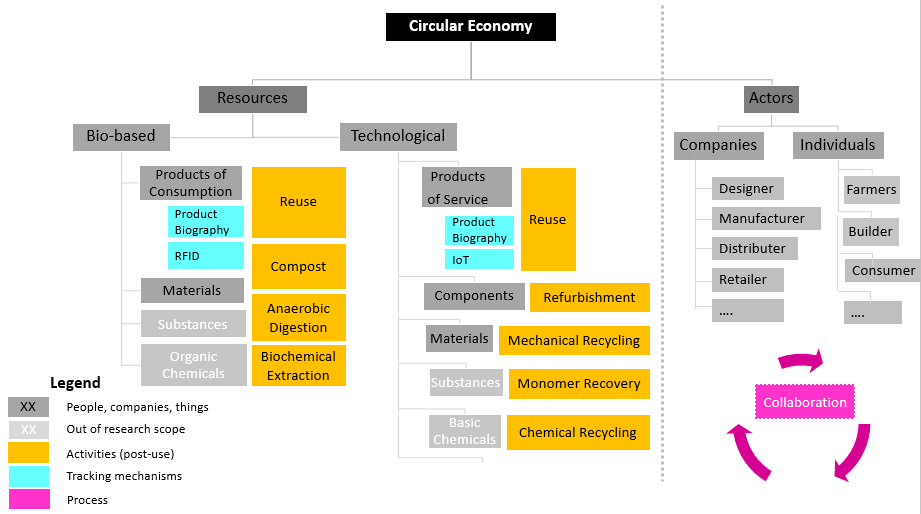

The Circular Economy ontology will be developed with products as the main focus unit, since product passports will account for the main data source. The passports should store information about the product provenance and the product qualities.

-

Product provenance: a supply chain sequence that details the companies or individuals involved in the product’s creation. This will link to the company’s profile which annotates the company’s location, inputs, outputs, certifications (i.e. Fair Trade) and post-use activities (along with the reverse logistics mechanisms) offered by the company. Moreover, for the product’s use stage, the owner will be annotated for the different use cycles.

-

Product Qualification: the characteristics related to the availability, condition and location of a product are stored [4] . This section will also annotate possible post-use activities for a product which will ultimately link to the post-use activities offered by companies.

The following competency questions incorporate the previous concepts and determine the scope of the ontology that will be developed:

-

Which companies produce a jeans (product) composed of recycled denim (material)?

-

Which companies generate outputs (blue dyed water) that can be used as input by Mud Jeans (company) for repairing (activity) jeans (product)?

-

Which products (jeans) are in good state (condition) and are available for reuse (post-use activity) on a specific city (Utrecht)?

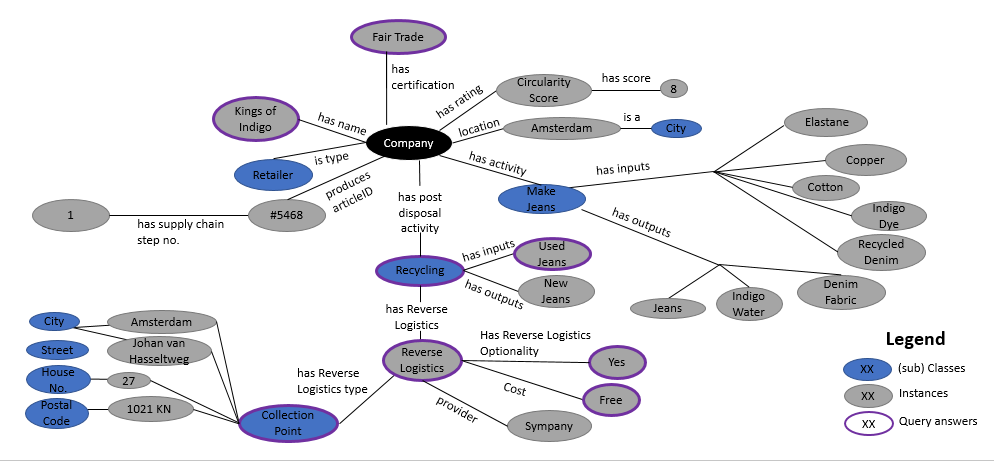

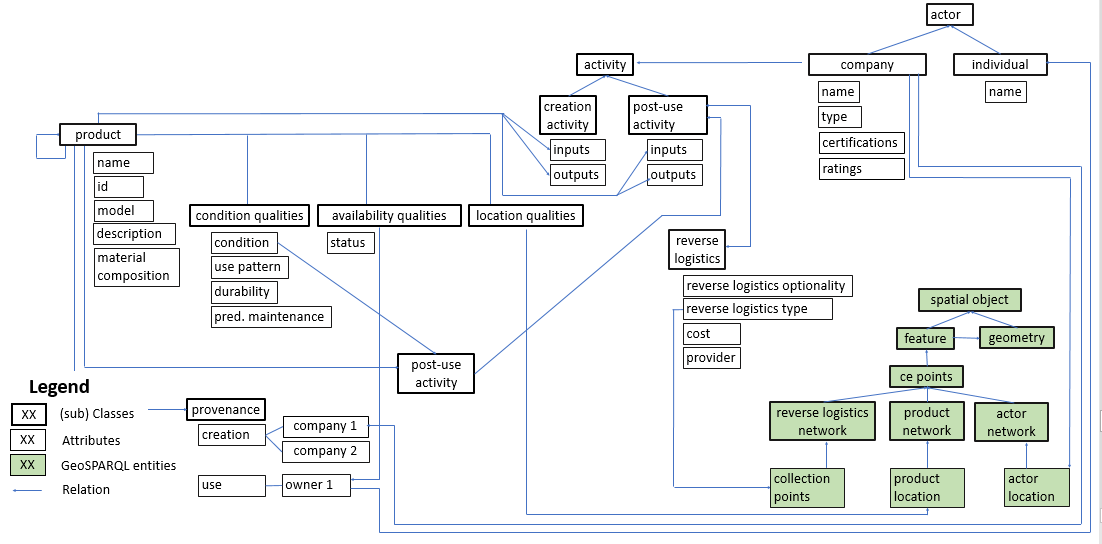

Figure 2 shows a representation of the Circular Economy Ontology. Actors and products will be related through the post use-activities, and the product provenance. Spatial features will be created for the actors’ and products’ locations, and the reverse logistics network.

Extending the Good Relations [6] ontology will be considered by adding extra properties to the BusinessEntity (equivalent to actor) and ProductOrService (equivalent to product) classes. For ProductOrService, the extra properties encompass the qualities, provenance, composition and its post use activity. For BusinessEntitiy, the extra properties deal with the activities offered by the company and the reverse logistics.

Depending on how the ontology will be implemented, the CE taxonomy ( Figure 1 ) could be converted to a dedicated ontology that works in combination with the GoodRelations extended ontology mentioned above; thus handling two separate ontologies like recommended by GoodRelations implementation. In this way, actors and their product exchanges will be kept on a more general level following the GoodRelations specifications. Whereas specific classes and instances for the post-use activity types and their corresponding inputs (bio-based or technological materials) would be encoded separately on an ontology exclusively for the CE materials and post-use activities. The advantage of this approach is that using the GoodRelations extended ontology makes use of functionalities already present in the existing ontology. Otherwise, the other approach would be to develop a complete CE ontology without extending the GoodRelations ontology.

Finally, in terms of spatial information, resources will be annotated using the GeoSPARQL ontology [11] for features and geometries.